ABOVE: Three versions of one of the ventilator models developed by Alher Mauricio Hernandez’s team at the University of Antioquia

ALHER MAURICIO HERNANDEZ

While no single idea or approach has successfully spelled the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, many scientists—including some with no previous experience in virology, medicine, or public health—have changed focus to try to fill needs they saw in the response to the virus.

Last July, The Scientist reported on some of these efforts: a project to design low-cost ventilators for manufacture in Colombia, a device to detect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, a volunteer network to assist fellow researchers, and a homegrown COVID-19 test in India. A year later, we catch up with some of the organizers of these projects for an update on how their work is going.

Colombia gets its own ventilators

When mechanical engineer Julian Echeverry of the University of La Sabana spoke with The Scientist last year, his team had just spent three months developing a ventilator that could be made in Colombia for $3,000 and had successfully tested it on a pig. Then, last August, it was tested on a patient for the first time. “Julian wrote us through WhatsApp, and he mentioned, ‘Okay, so it’s time zero. First patient is going to be connected. Start praying,’” says Andrés Ramirez, a professor on the team whose background is in robotics. Ramirez couldn’t sleep that night, he recalls.

The test was successful. The team received regulatory approval from INVIMA, the Colombia National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute, to conduct a small clinical trial, and distributed more ventilators in the meantime on an emergency basis. About 400 of the ventilators have now been made, 60 of which have been distributed to hospitals around Colombia. It’s a rewarding outcome, says Echeverry, who before the pandemic worked on automotive engineering. “As an engineer, you are never expected to save anyone’s life. . . . After developing this ventilator, we can happily say that we have saved many people’s lives. . . . It really touches your heart and soul.”

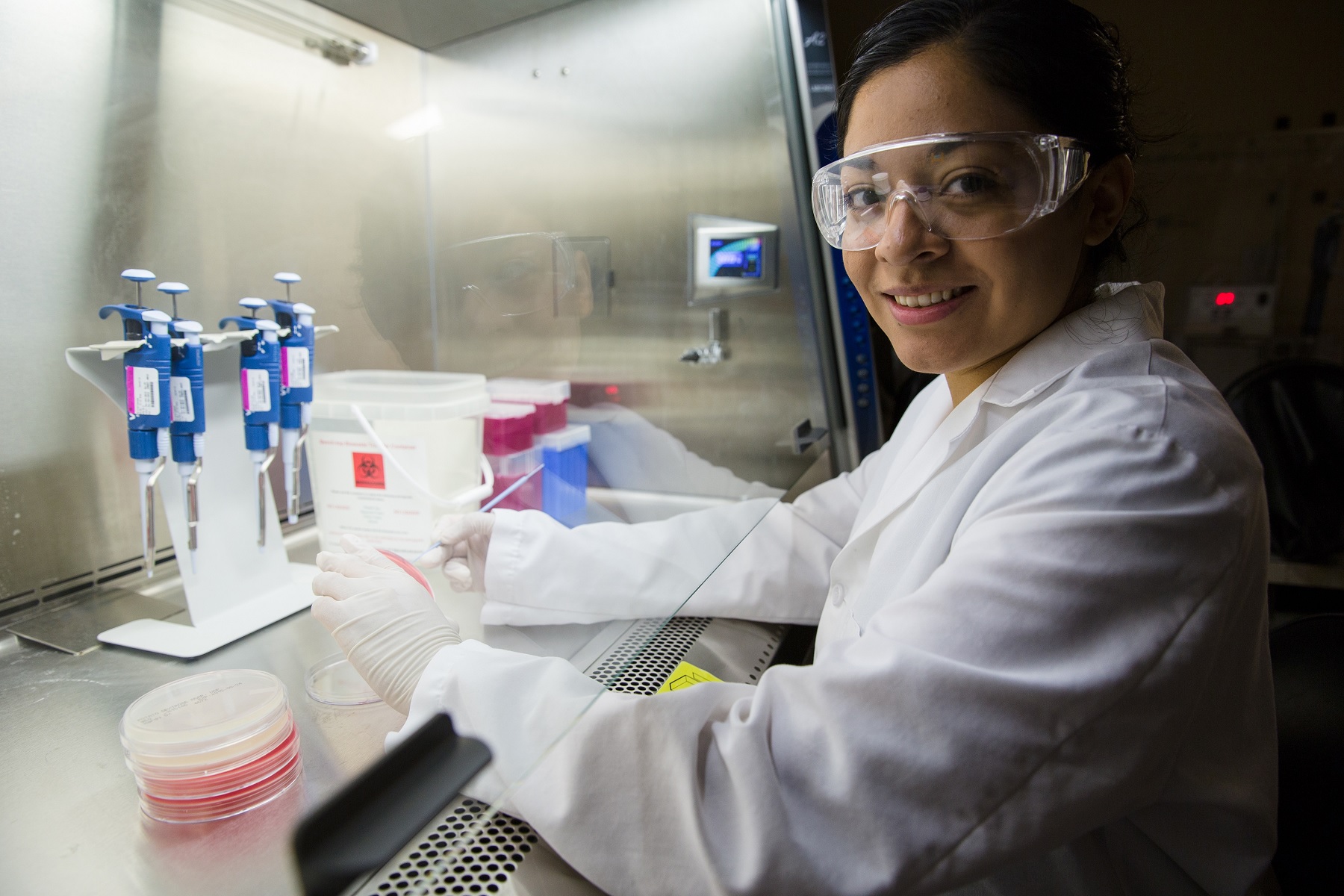

Several other university-based teams in Colombia launched projects to design their own ventilators last year. Another project, in which universities and companies collaborated to develop three different ventilator models in case the parts needed to make one should become unavailable, had also started testing on pigs when The Scientist reported on it last year. Since then, the models have passed the first phase of clinical testing and are awaiting approval for the second, says Alher Mauricio Hernandez, a biomedical engineer at the University of Antioquia. Some ventilators have already been sent to hospitals for use if other ventilators are not available, he says, and he’s recently heard from several hospitals that they have used the ventilators on patients for the first time.

Hernandez says he’s disappointed in what he sees as a lack of government support for the project, which has instead been funded by donations from companies. Nevertheless, he adds, “we feel very lucky to have this kind of opportunity to contribute to our society, as well as relief.”

Researchers mine sewage for SARS-CoV-2 public health data

Biobot Analytics, a company that provides wastewater monitoring services to communities interested in harnessing this source of public health information, has seen a surge in interest in the use of sewage testing for public health since the start of the pandemic.

The company has been around since late 2017, but the idea was initially slow to catch on, says Mariana Matus, a cofounder of the Cambridge, Massachusetts–based startup. While the company’s vision was to test for a range of public health–related indicators in the effluent, a big focus at the outset was on detecting signs of opioid overuse so that leaders would know which areas in their communities were most in need of resources for intervention, she says. Still, “one of the challenges we were facing early on . . . was simply raising awareness for the fact that this technology exists, and what it can accomplish,” Matus explains.

At the beginning of the pandemic, though, officials began seeking data on SARS-CoV-2 in their communities’ wastewater to complement information from clinical testing for the virus, she says. Between March and May 2020, the company’s customer base expanded 15-fold, and now includes communities in more than 20 states. The approach has taken off elsewhere, too: many universities are now performing their own wastewater monitoring for outbreaks on campus, while the UK and several other countries have launched national sewage-testing programs to help detect new outbreaks.

Currently, Biobot’s clients send samples to the company’s lab, which analyzes them using quantitative PCR and sends reports on the samples’ quantities of viral RNA back to clients the following day. The company won a US Department of Health and Human Services contract to establish a national disease monitoring program earlier this summer, and Matus says it remains interested in finding an assay that’s faster than PCR, but hasn’t been able to identify one yet that has sufficient sensitivity.

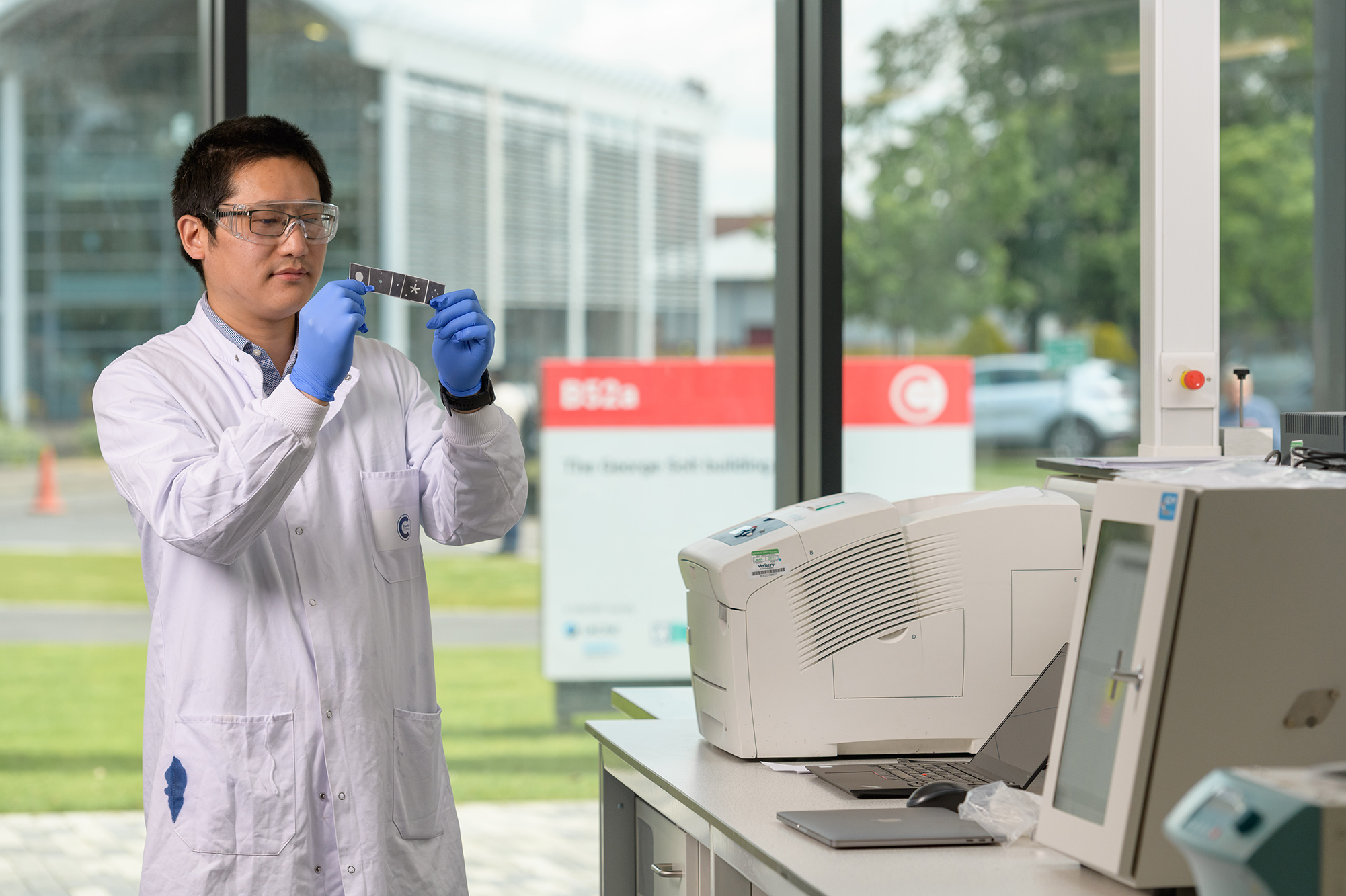

One candidate for a faster and more sensitive SARS-CoV-2 sewage test, described by The Scientist last year, was designed by a team led by Zhugen Yang of Cranfield University in the UK. The test, which can be performed outside of a lab and uses a DNA-amplifying technology called loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), produces a result in a matter of hours in the form of a color change related to the concentration of virus; users can evaluate this color change by eye to get a positive/negative result, or using their phone’s camera to obtain more quantitative information.

The team has since validated that the test is accurate enough to move forward with, Yang says, and the researchers are now working on identifying a commercial partner that could manufacture the disposable sensors it requires, and on sourcing the reagents needed to scale up the test. Ultimately, Yang says, he hopes the test can help lead to a better understanding of the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2’s spread and thus to effective interventions.

For her part, Matus is already looking beyond the pandemic to a future of more-comprehensive wastewater monitoring. “We see this COVID-19 product evolving into a biosurveillance platform for COVID and for other viruses of public health importance,” as well as opioids, she says.

Crowdfight works toward normalizing requests for help

Born out of researchers’ desire to help combat the pandemic, Crowdfight COVID-19 matches volunteers with requestors who need someone with a particular skill set, or simply extra time or a certain reagent on hand, to aid a scientific project. Founded by animal behavior researchers Daniel Calovi of the Max Planck Institute for Animal Behaviour near Konstanz, Germany, Sara Arganda of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos in Madrid, and Alfonso Pérez-Escudero of the Research Center on Animal Cognition and Center for Integrative Biology in Toulouse, the organization now has nearly 35,000 registered volunteers and has successfully fulfilled or partially fulfilled more than 110 requests. Pérez-Escudero’s favorite success story involves a research team in Hong Kong that asked for volunteers to conduct a literature review on the molecular biology of SARS-CoV-2, which grew into two reviews in Cell Press journals coauthored by the volunteers and the requestors.

This is the important thing, to tell people, ‘Hey, you can ask for help, and people will help you.’

—Alfonso Pérez-Escudero, Research Center on Animal

Cognition and Center for Integrative Biology

In late 2020 and early 2021, Crowdfight had one full-time and one half-time employee, thanks to funding from the EU. That funding has been used up, and the network is back to being entirely volunteer-run, although Pérez-Escudero says they’re seeking more stable funding for the longer term. In the meantime, Crowdfight is expanding. When he spoke with The Scientist last year, Pérez-Escudero was already interested in applying the volunteer network approach into areas of science beyond COVID-19. He explains that, through the response to the project, “we found that actually people want to help even if it’s not for the pandemic, because in science we are working for a common goal.” The service opened to non-COVID–related research in February.

The organization also hosted an online symposium last month aimed at fostering a culture shift in the scientific community toward making it more common to ask for or receive help from one another. This is different from collaborations in which, say, two labs are both interested in exploring the same research question and publishing a study together, Pérez-Escudero says. He wants to see more researchers reaching out to an expert on a particular protocol for advice as they begin a new project, for example. The main hurdle to Crowdfight’s widespread use, he says, has been scientists’ hesitancy to make such requests—and that was the motivation for the symposium. “Now we realize that this is the important thing, to tell people, ‘Hey, you can ask for help, and people will help you.’”

Churning out tests in India

When we spoke with staff at India’s MyLab Discovery Solutions last spring, the company had recently rolled out India’s first home-grown test for the novel coronavirus. Dubbed PathoDetect, the PCR test kit sold for about $16 at the time; now, it’s down to about half that because the company has scaled up production and because the cost of raw materials for the kits has gone down, says Gautam Wankhede, MyLab’s director of medical affairs. “By July or August [last year], we had more than 500 labs across the country which were doing these tests.”

See “Assay for Sickle Cell Anemia Is Repurposed to Diagnose COVID-19”

But the company saw room for improvement, Wankhede says, because there was a shortage of trained personnel to run the tests, and because labs were under pressure to perform more tests as the number of COVID-19 cases ramped up in India last July and August. It happened that MyLab had for several years been working to develop a “lab in a box” that would automate the process of preparing a sample for PCR testing. The company rolled out the technology last summer, and has so far sold about 100 units to labs across India; it deployed dozens more last fall in minivans that serve as mobile testing labs in rural areas, Wankhede says. MyLab also offers antigen tests, including a version that can be administered at home. Neither this test nor the PCR test distinguish among variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Overall, Wankhede says, the testing situation in India has improved considerably since the start of the pandemic. Apart from five or six weeks at the height of the surge in April and May of this year, test results are generally available within 24 hours even outside of major cities, he adds. “I’m sure we have saved a lot of lives,” he says. “It’s a good feeling that we were able to make an impact.”