WIKIMEDIA, BIOMED CENTRAL; SÁNCHEZ-SORIANO, TEAR, WHITINGTON, PROKOP The functions of miniature neurotransmission, in which presynaptic neurons spontaneously release synaptic vesicles that induce postsynaptic neuronal activity, have eluded neuroscientists since the process was first discovered in the early 1950s. Some have simply considered miniature neurotransmissions—or “minis,” which have been found at every synapse studied—to be byproducts of neurotransmission evoked by action potentials. But in recent years, others have presented evidence to suggest that minis are functional, influencing the production of proteins at synapses, among other things.

WIKIMEDIA, BIOMED CENTRAL; SÁNCHEZ-SORIANO, TEAR, WHITINGTON, PROKOP The functions of miniature neurotransmission, in which presynaptic neurons spontaneously release synaptic vesicles that induce postsynaptic neuronal activity, have eluded neuroscientists since the process was first discovered in the early 1950s. Some have simply considered miniature neurotransmissions—or “minis,” which have been found at every synapse studied—to be byproducts of neurotransmission evoked by action potentials. But in recent years, others have presented evidence to suggest that minis are functional, influencing the production of proteins at synapses, among other things.

Working with live Drosophila, Columbia University Medical Center’s Brian McCabe and his colleagues now demonstrate another role for minis: regulating the structural maturation of glutamatergic synapses. Their work was published in Neuron today (May 7).

“The paper is very exciting . . . [and] extends our previous understanding of miniature neurotransmission in important ways,” said Michael Sutton, an associate professor at the University...

Previous reports demonstrated that spontaneous neurotransmission differs from evoked transmission. In February, for example, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, showed that different Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) synapses exhibited one mode of neurotransmission more often than the other.

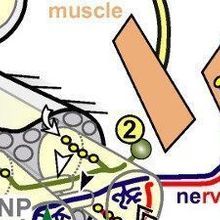

Studying Drosophila larvae, McCabe’s team experimentally knocked down each form of transmission at glutamatergic NMJ synapses and observed the effects. The researchers found that loss of minis alone caused defects in the development and maturation of these synapses, whereas knocking down evoked neurotransmission did not. And stimulating miniature transmission even promoted normal synaptic growth.

Researchers have often focused on initial synapse formation, McCabe said, and for that, miniature neurotransmission does not appear to be essential. “But for subsequent development of those synapses, then it is required,” he said. “That’s a new discovery.”

McCabe and his colleagues further investigated how minis influence synaptic development using Drosophila mutants in which some of the fly’s postsynaptic glutamate receptors were inhibited. They found that minis regulate the growth of local synaptic terminals by activating a signaling pathway involved in presynaptic neuronal development.

These experiments “beautifully dissociate the role of minis and evoked transmission in developmental maturation of the Dropsophila NMJ,” Sutton wrote in an e-mail to The Scientist. “The authors very elegantly demonstrate that it is not the amount of activity at synapses that controls maturation, but rather, it is the nature of the activity (evoked versus miniature events) that is important.”

McCabe’s team is now working to better understand how small, spontaneous events could have such profound effects on synaptic development. The researchers are also investigating the effects of minis in the adult fly brain. Moreover, how exactly minis function is still an open question.

“Maybe minis are a separate layer of communication that might allow synapses to remain connected within information flowing between them,” said McCabe. “If you think about your grandmother, who maybe you haven’t thought about for a long time, that memory is still there, those neurons are still connected,” he said. “But if you’re not retrieving that information and using the circuits, how do those synapses stay connected?” Minis may play a role in maintaining such connections, McCabe speculated.

“This paper adds to an emerging view that miniature events and evoked transmission have unique functional roles in neural circuits,” Sutton told The Scientist. “Clearly, understanding the molecular mechanisms whereby miniature events signal in postsynaptic neurons is an important area of future research.”

B.J. Choi et al., “Miniature neurotransmission regulates Drosophila synaptic structural maturation,” Neuron, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.012, 2014.

Interested in reading more?