ABOVE: The man-of-war fish (Nomeus gronovii), a species of medusafish, near the tentacles of a siphonophore. Linda Ianniello

EDITOR’S CHOICE IN EVOLUTION

The paper

M.N.L. Pastana et al., “Comprehensive phenotypic phylogenetic analysis supports the monophyly of stromateiform fishes (Teleostei: Percomorphacea),” Zool J Linnean Soc, doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab058, 2021.

Fishes such as driftfishes, butterfishes, and barrelfishes—traditionally grouped as medusafishes (suborder Stromateoidei)—share a gizzard-like “pharyngeal sac” lined with tooth-like projections that grind up food. But despite their shared morphology, recent molecular studies have placed them into multiple groups rather than one evolutionary lineage. “Conflicts between morphology and DNA-based hypotheses are particularly striking for this group, and their resolution represents one of the biggest challenges of the systematics of bony fishes,” says Murilo Pastana, an ichthyologist at the National Museum of Natural History.

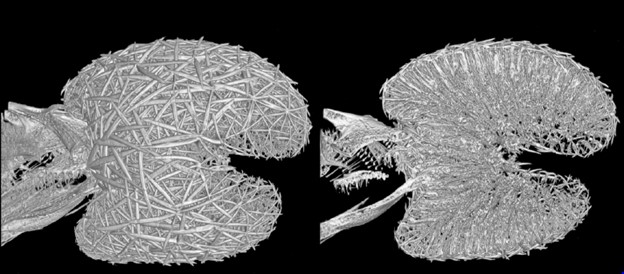

To determine whether the 15 genera of medusafishes are in fact closely related, Pastana and his colleagues conducted the largest morphological study of the group to date, examining more than 200 characteristics. Through dissection, staining, and imaging, they detailed the internal and external structures of more than 20 species.

The team found that, in addition to pharyngeal sacs, medusafishes share a system of canals and pores that supply their skin with mucus. This mucus may protect young individuals, which frequently hide near stinging animals like jellyfishes, says Pastana. His data suggest that, despite the molecular contradictions, medusafishes do share a common ancestor, one that possessed a pharyngeal sac, skin mucus, and 11 other features, including 18 pectoral-fin rays and a unique nerve branching pattern.

Dahiana Arcila, an ichthyologist at the University of Oklahoma who researches phylogeny using molecular tools and wasn’t involved in the study, explains that some of the conflicting evidence stems from the taxon’s history. “Their rapid evolution after the end-Cretaceous extinction makes their relationships particularly challenging to sort out,” she says. Both Pastana and Arcila agree that, although their approaches differ, the combination of morphological and molecular data will ultimately solidify scientists’ understanding of fish diversity.