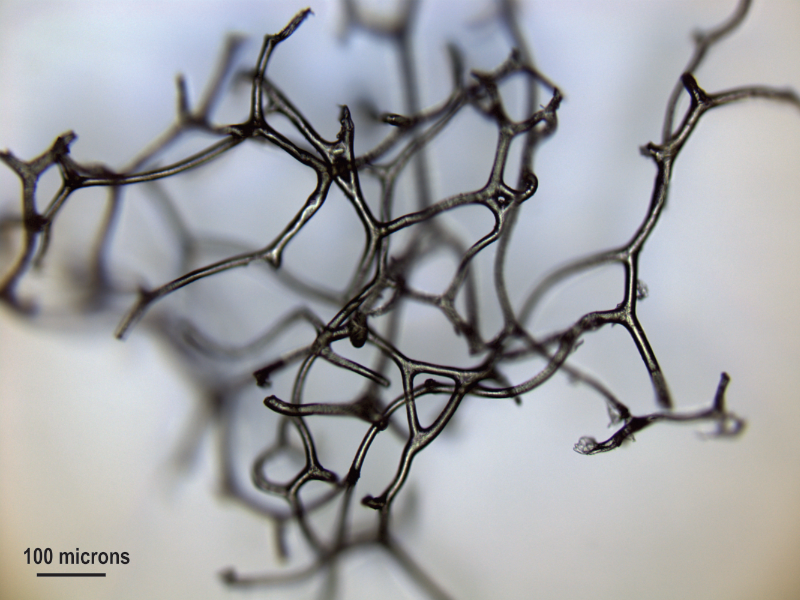

ABOVE: A low-magnification view of the connected network of tunnels that form a putative sponge protein skeleton fossil found in an 890-million-year-old rock. The field of view is about 9 millimeters.

EC TURNER

Scientists predict that sponges—among the most basic animals—arose a few hundred million years before the occurrence of the oldest confirmed fossil specimens, which date to about 500 million years ago. Now, in a study published today (July 28) in Nature, Elizabeth Turner, a geologist at Laurentian University in Canada, identified structures in 890-million-year-old fossils of organisms similar to modern bath sponges, potentially pushing back the emergence of the animals to at least that long ago.

The work “gives good evidence that there were sponges living 890 million years ago, and that’s much older than any firm recognition of fossil sponges so far,” says Robert Riding, a geologist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville who did not participate in the study. That record, until today, was held by fossils of purported sponges that are about 635 million years old, although their animal identity is not accepted by all researchers in the field.

In fact, if the new fossil finds are confirmed to be sponges, “they would be not just the oldest sponges; they would be the oldest animals,” Riding points out. To find any fossil more than 200 million years older than previous animal fossils “is significant,” he says.

The discovery actually happened more than 10 years ago, when Turner was a graduate student at Queen’s University in Canada. Her thesis project focused on reef rocks, and she encountered the material described in the current paper accidentally in a tiny number of the specimens. “I thought I had an idea of what it might be, but there was no real way of proving it at the time,” she tells The Scientist. Over the past few years, other researchers published papers about how sponges get preserved in the rock record. The “accumulation of a critical mass of those papers that provided me, as of now, with a sufficient foundation to present my own work, which is comparable, but in rocks that are much older,” she explains.

In the study, Turner used light microscopy to examine 30-micron thick slices of 890-million-year-old rocks from fossilized reefs in Northwestern Canada, originally laid down as calcium carbonate deposits by cyanobacteria. In rare slices of rock, she found microscopic networks of connecting tubes of calcium carbonate that branch to form irregular three-dimensional shapes with similarities to modern bath sponges. Other researchers have confirmed similar structures as sponge-derived in younger rocks. This type of sponge doesn’t incorporate calcium carbonate itself, instead, it has a tough protein-based skeleton during life that after death is slow to decay and thus calcified more slowly than the surrounding material.

“There’s room to be skeptical,” says Drew Muscente, a paleontologist at Cornell College in Iowa who did not participate in the study. His work has focused mostly on the skeletons that some sponges produce, called spicules, usually made of silica or calcium carbonate. “These are unambiguous structures that sponges produce, so you would imagine some sponge at some point in Earth's history—perhaps the earliest sponges—had these structures that you identify,” he adds. It’s trickier to identify bath sponges because they do not produce spicules.

“Could these structures be sponges? Yes. Are we sure they’re sponges? I'm not,” Muscente adds, acknowledging that he may be “overly conservative,” but that the evidence is circumstantial at this point.

On the other hand, if researchers “embrace these structures as the oldest sponge fossils, it will help really shed light on, not just the origin of sponges, but the timing of the origin of animal life as a whole, because these would be the oldest animal fossils, period,” Muscente says.

“It’s really a milestone,” says Joachim Reitner, a paleontologist at the University of Goettingen in Germany. Reitner did not participate in the work, but has previously published studies identifying similar sponges in younger fossils. The paper serves as evidence that this type of sponge, and also the complex genetic tools needed to form their protein skeleton, was already present 890 million years ago, he adds. “It means that the origin of the of the animals was much earlier . . . maybe a billion years ago or so.”

Turner says a much older origin for animal life shouldn’t come as a surprise, as it’s been predicted by estimates of when genes evolved, but “what's going to be challenging for the scientific community is the fact that the age of these rocks—890 million years old—is well prior to two extremely important, dramatic geological events in Earth’s history . . . that other people have assumed inhibited either the evolutionary appearance of animals or their diversification or both.”

The Neoproterozoic oxygenation event, for instance, when it’s believed that oxygen in the atmosphere and deep ocean increased dramatically, is thought to have happened between 800 and 540 million years ago. Scientists have thus predicted that animal life would have been difficult before that.

“But sponges are the most basic animal type that we know, and some of them in the modern world and in the rock record have comparatively low oxygen requirements,” says Turner. It’s possible that sponges did appear 890 million years ago in a low-oxygen world, but survived due to their close proximity to the oxygen-producing cyanobacteria that made the massive reefs where these fossils were found.

“Animals emerged evolutionarily long before the first traditional animal body fossils appear in the rock record, so there was a long prehistory to animal evolution, which is not well recorded, and really needs further work,” she adds. “The rock record really needs to be much more thoroughly interrogated.”